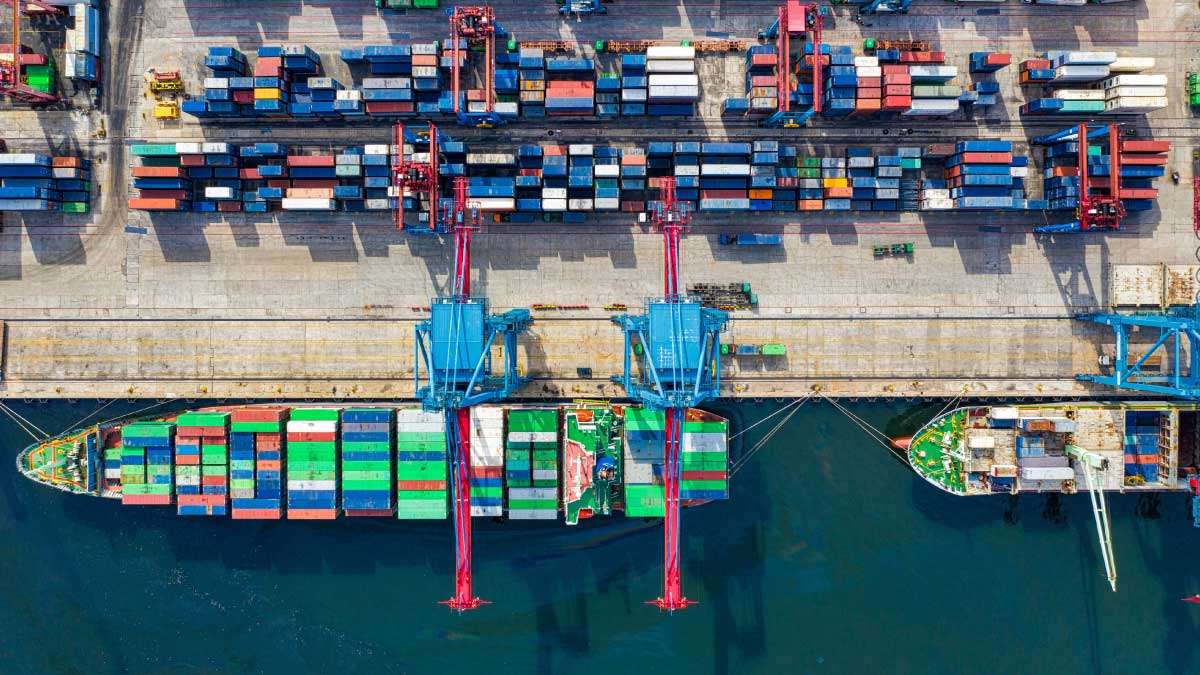

Red Sea Shipping Disruption and International Trade

Over 80% of global trade is carried out by sea, and as the current state of affairs in the Red Sea demonstrates, interruptions to shipping routes can have far-reaching consequences. Policymakers and market observers have focused on the immediate effects of longer delivery times and higher fuel prices, but these are only the beginning. Businesses will encounter difficulties with rising insurance premiums, declining ship security, and broader environmental, social, and governance (ESG) effects as the upheaval persists. The difficulties increase in number as it goes on and cover a larger area.

Additionally, the Red Sea situation offers a glimpse of geopolitical risk in the future. As one of the primary commerce routes connecting Asia, the Middle East, and Europe, the Red Sea is estimated by Clarksons to account for 10% of global trade volume. This accounts for 20% of all shipping containers, 10% of oil carried by water, and 8% of LNG. But the significance of the Red Sea is not unique: There are strategic chokepoints for marine traffic everywhere in the world, from naturally occurring straits and funnels to canals. Actors will start to think about their capacity to pull out something similar when they see the effects of Houthi threats and attacks. The possibility of a worldwide economic crisis if similar tactics were applied to other busy routes, including the South China Sea, is especially concerning.

Policymakers must be aware of the long-term effects of disruptions to important maritime routes in order to plan ahead and avert these disruptions. Investigating the potential effects of the Red Sea disruption, contingent on its duration is helpful in achieving this goal. One of the biggest problems in the medium run will be ships that are just placed in the incorrect locations. Supply networks have changed to accommodate just-in-time tactics. This puts pressure on the supply chain’s delicate balance, which is particularly noticeable between containers and ships.

Immediate Effects of Red Sea Shipping Disruption

Ship availability

Ports have restricted physical space as well as a limited number of berths, many of which are size restrictions. Berths are booked months in advance to schedule appropriate port-side support for offloading, reloading, and refueling. These berth reservations determine when containers and other items are delivered by ground.

The delays cause ripple effects at the ports as ships divert or take alternate routes. Goods and containers clog the ports while they wait to be shipped onward when ships miss their berths. Vessels that reroute or anchor cause disruptions to the availability of transit options from ports, in addition to slowing down supply chains. Ships that have been rerouted may overrun alternate ports, causing backlogs at berths and obstructed transit into and out of the ports.

Similar to the COVID pandemic, ship arrival delays cause containers to rapidly accumulate in ports. This is made worse by the fact that ships are frequently told to anchor or redirected in an effort to reduce the risk.

Insurance

The practice of ships “going dark,” or cutting off their transponders from tracking systems, has long been dangerous. This is done in order to facilitate a variety of illegal acts, such as avoiding fines, IMO regulations, or contractual restrictions. Due to its strategic location in relation to nations subject to trade sanctions, the Red Sea has long been a hub for this kind of business. Insurance rates for ships passing through the region reflect this. Premiums are expected to rise as ships employ this tactic to try and avoid being attacked by Houthi forces. The cost of insurance will go up due to that additional risk.

The fact that traveling around the Cape of Good Hope is intrinsically riskier than traveling via the Red Sea will have an impact on insurance costs as well. From a logistical standpoint, ships must not only travel a lengthier journey but one that is impacted by difficult weather patterns. While ports on Africa’s western coast are frequently more prepared to handle Capemax ships, this also creates opportunities for illegal activity both at and from the ports. Geographically, the particularly violent West African piracy poses a greater threat to shipping. High levels of instability in the region and the little state power available in the event of a crisis further complicate this.

If the disruption continues for months, there will be an increase in shipping costs due to backlogs in ports and lowered ship availability. This will increase the carbon footprint as ships will have to take a longer route and will burn more fuel.

Conclusion

Whether we are dealing with a small annoyance or a more significant obstacle for international shipment will become clear in the upcoming weeks. But similar to the COVID-19 epidemic, this event has highlighted the value of maritime trade routes and offered insight into geopolitics’ future. The capacity to exert influence over international economic arrangements is increasingly available. States need to modify their foreign policy plans to account for the fact that certain actors, both state and non-state, might have a disproportionate influence on world commerce.